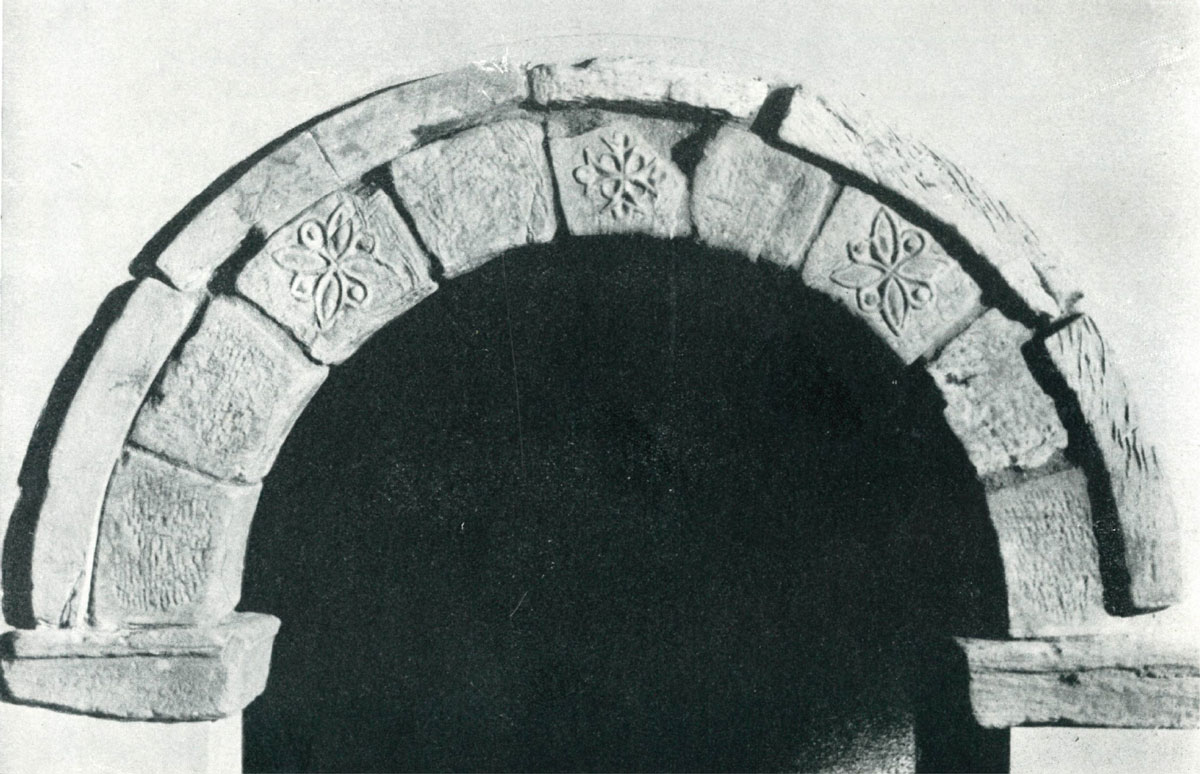

Southern gate of the Church of Saint Raphael

The Excavation of Tamit: A Race Against Time

In 1964, the Mission of Sapienza University of Rome began its excavation work in Tamit, an important urban settlement in Lower Nubia. Located about 9 km south of Abu Simbel, Tamit had already been visited and partially described over the 30s of the 1900s, by the famous engineer and archaeologist Ugo Monneret de Villard (Milan, January 16, 1881 - Rome, November 4, 1954), who was very active in the Egyptian and Sudanese Nubia.

The Mission, directed by Sergio Donadoni, Professor of Egyptology at Sapienza, was also composed of Egyptologists, Edda Bresciani and Sergio Bosticco, the archaeologists, Anna Maria Roveri and Ida Baldassarre, and topographer and draftsman, Giuseppe Fanfoni.

The excavation of Tamit was, more than any other, strongly conditioned by the construction of the High dam of Aswan. Sergio Donadoni, in fact, had obtained the concession precisely in the context of the documentation of the Nubian sites inexorably destined to disappear under the lake, an activity that should have accompanied the better known and spectacular rescue and displacement of the great templar complexes, including Abu Simbel.

When excavations began (August 26, 1964), it was believed that the Nile would grow at a slow pace, allowing new discoveries to be documented with due calm. This was not the case: within a few days the water had increased dramatically, causing the rapid collapse of the adobe structures and forcing the mission to move by boat from one side of the site to the other.

At the conclusion of the short and complex mission (September 16, 1964) Donadoni commented:

When we left Tamit’s camp, the city was reduced to an archipelago formed by its highest parts, and the brick walls were collapsing, lapped by the current of the river

(S. Donadoni, Tamit (1964), Roma 1967, p. 15)

The Nile before the filling of the reservoir of Lake Nasser

A Town Without Walls

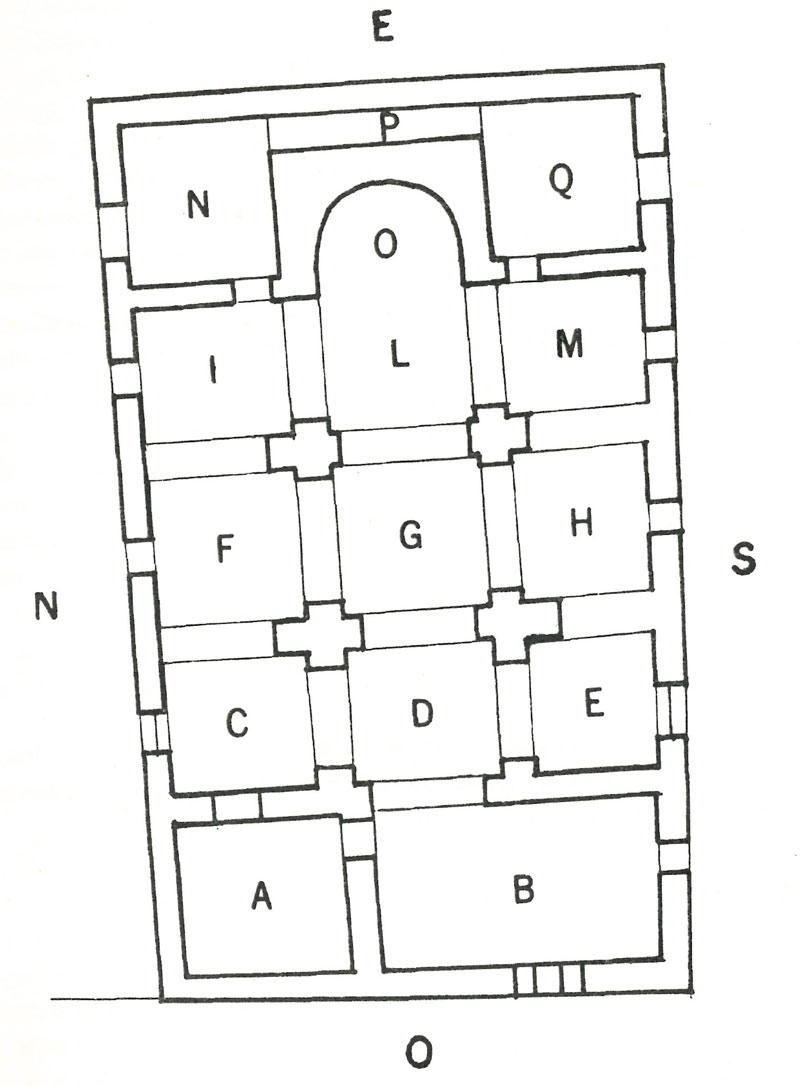

Thanks to the realization of the overall topographical survey of the site and to a series of excavations in some points considered strategic, it was possible to establish that the city was lacking fortification walls and also major roads; on the other hand, the residential settlement, in its later phase, had at least eight churches, three of which were extra-urban (defined as the “group of contiguous churches”), three semi-peripheral (two of which dedicated respectively to Saint Raphael and the Angels), one located in the cemetery area and, finally, only one (Saint Paul), not large, located in the centre of the town.

It was immediately clear that the presence of so many churches was an anomaly, bearing in mind also the fact that Tamit was never an episcopal see. Furthermore, none of them was attributable to a monastic context, therefore such a large number of ecclesiastical structures could only be explained by the fact that Tamit must have been a significant religious and pilgrimage centre, even if it was never possible to verify this hypothesis in detail.

As for the houses, all of quadrangular shape, they were a range of sizes (from 21 to 143 m2), but all on two floors, connected by an external mud brick staircase, the upper one of which was covered by a barrel vault.

The city was also equipped with three cemeteries, of which the oldest was located close to the town, while the other two were located at some distance from the settlement.

The physical characteristics of the city, and the absence of walls in particular, led to the deduction that its foundation should be dated between the eighth and ninth centuries, when the defensive requirements that had characterized the first phase of the Christianization of Nubia had failed. The domed roof, ascertained for at least three churches, also led to the belief that they should be dated, at least in their later phase, to the eleventh century.

Plan of the Church of Saint Raphael

The Inscriptions and the Paintings

Although Tamit did not ofer up many finds useful for the reconstruction of daily life in the settlement other than pottery, there are, on the other hand, numerous inscriptions and pictorial remains that could be recovered.

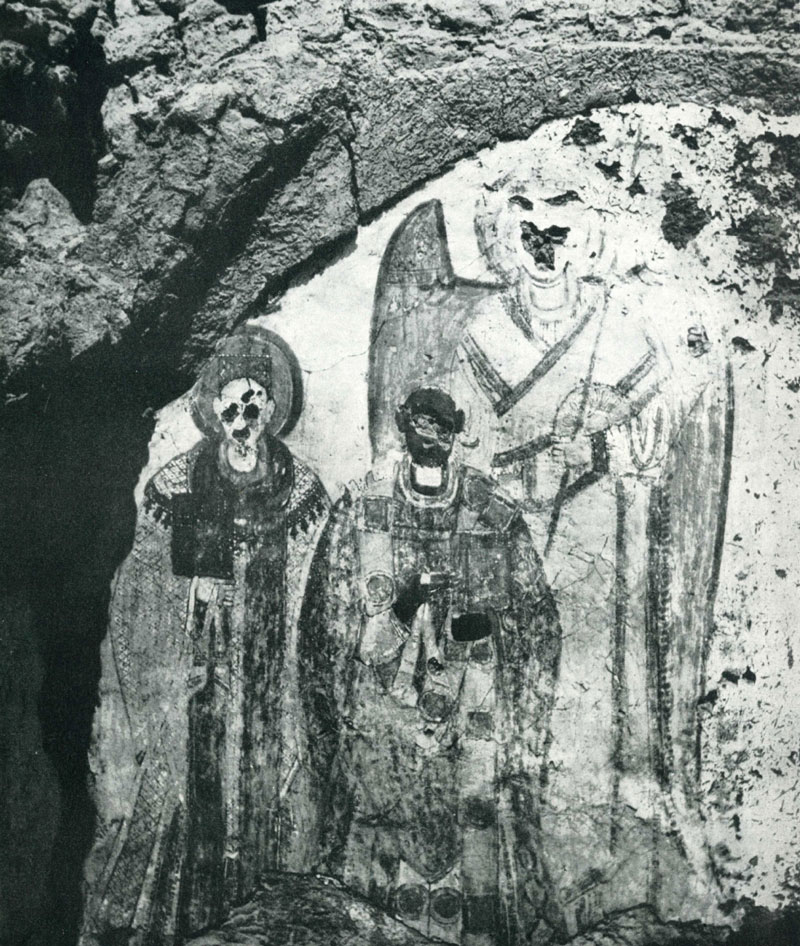

As for the epigraphic material, it presented varied functional and linguistic characteristics, which express well the complexity of the culture of mediaeval Nubia. Greek, Coptic and Old Nubian were combined, both in the funerary inscriptions and in the captions of the pictorial cycles, as well as in the devotional texts. Many of these inscriptions were recovered, others only documented, due to the shortage of time and the logistical and environmental obstacles already described.

But it was, above all, the pictorial cycles, executed in tempera, that aroused the greatest interest. Some of them, documented by Monneret de Villard, were lost at the time of the 1964 mission. However, the team led by Sergio Donadoni was able to save numerous panels from the only four churches that appear to have been decorated, before the waters rose any further. In this undertaking, the presence in Abu Simbel — headquarters of the Sapienza mission — of the restorer of the Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte Ibrahim Abdelqader, who followed the work of the detachment and the first consolidation of the paintings, proved to be providential.

These paintings are now kept in the Coptic Museum in Cairo. These works of art can be dated between the ninth/tenth century and the fourteenth century. The dating depends on a comparison with other sites and monuments, including the famous cathedral of Faras, which was investigated in the same years by the Polish mission, led by Kazimierz Michałowski, and whose splendid paintings are today divided between the Sudan National Museum in Khartoum, and the National Museum of Warsaw.

A Nubian bishop sided by a bishop-saint and an archangel (Raphael?) located in the passage between rooms M and H

The Paintings of the Church of Saint Raphael

There is no doubt that the richest of Tamit’s churches, both from an architectural and a pictorial point of view, was the one dedicated to Saint Raphael. His paintings are certainly to be referred to several phases and the execution of some of them involved the plugging of doors and slit windows, a sign that the church itself was restored several times. The figures were always outlined in red or black and filled with unshaded bright colours.

One of the most interesting images – among the many that could be mentioned, often dedicated to holy knights – is the one that represents the saint to whom the church was dedicated. Raphael is standing, leaning against a long rod and dressed in a richly decorated dress. The archangel’s feet rest on a long beast (a dragon? a crocodile?) with its mouth wide open, from which a small bearded figure emerges with arms raised. To the right of the saint is the model of the church, which confirms the domed roof that once crowned it.

Equally remarkable is the representation of a dark-skinned bishop, not unlike a similar representation found in the cathedral of Faras and others from the church of Abdalla Nirqi, which demonstrates the independence of Nubia from Egypt in the formation of its own ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Archangel Raphael whose feet rest on a long beast (a dragon? a crocodile?) with its mouth wide open, from which a small, bearded figure emerges with arms raised.

An Exceptional Find

Of the three mediaeval cemeteries of the Tamit site, the so-called “western cemetery”, which is particularly extensive, overlaps a necropolis of the pre- and proto-dynastic period. In the so-called “tomb 10” a little globular vase was found that is to be referred to the culture of “Group A” (3800-3100 BCE), that is to say to the phase of occupation of Nubia, which saw the adoption of motifs and artefacts typical of early pre-dynastic Egypt (late Naqada II - Naqada III).

The little vase features a purplish-red decoration depicting boats with oars and cabins, separated by fan-shaped bushes. On one of the boats, a decoration in the shape of a bucranium can be seen at the stern. This is an exceptional find in Nubia, which demonstrates how the late ancient and mediaeval Tamit represented only the last phase of occupation of a site that had been fully involved in the socio-political and artistic phenomena of the dawn of Egyptian culture.

Little globular vase which is to be referred to the culture of “Group A” (ca. 3300 BCE).