View of the eastern side of Jebel Barkal from the temple area, 1973 (Archive MVOEM)

From the Church of Sonqi to the Mountain of Jebel Barkal

In 1973, after completing the work at Sonqi Tino and following a brief survey conducted in 1970-1971, the Mission of Sapienza University of Rome started a new excavation project in the archaeological area of Jebel Barkal, about 400 km north of Khartoum, near the modern town of Karima. The importance of the site, which is named after the local sandstone mountain (jebel, جبل) standing out against the surrounding desert, is well summarised well in a short promemoria prepared by Sergio Donadoni in December 1972, just before the beginning of the first season of fieldwork:

It is a monumental area, among the most important in Sudan, with a full series of Egyptian and Meroitic temples (in part already excavated and published), with royal and private necropolises (less explored than the sanctuaries), with the remains of a city (still largely unknown): it is the ancient Napata, which was the capital at the time of the ‘Ethiopian’ dynasty (i.e., the 25th dynasty) and had been a prominent centre since the 18th dynasty, as the epigraphic and sculpture material show.

birth of the new archaeological enterprise was the direct outcome of the positive engagement of the Roman mission in the salvage of the church of Sonqi, and was carefully designed as a long-term research programme. This enlarged perspective clearly emerges from the early exchanges between Donadoni and the Sudanese authorities. In a letter addressed to the then Commissioner for Archaeology, Sayed Negmeddin Mohammed Sharif (8 April 1971), the Italian scholar explicitly remarked that

A long term work in the Sudan seems to me the normal development of the good experience of the last years’ excavations

Of the two potential sites identified at that time, Jebel Barkal and Kawa (near Dongola), the former was finally selected for both practical and methodological reasons. The prospective mission was thus envisaged as an active fieldwork where high-level research could be conducted and young scholars could be trained, combining the skills of egyptologists, archaeologists, architects and restorers. It was within these premises and with such goals that the Mission of Sapienza was fully established and settled down in Karima in March 1973. It was also thanks to the relentless efforts of P. Giovanni Vantini, who was of crucial help with the practical arrangements, but was unable to join the work.

The following archaeological activity was then conducted uninterruptedly for more than thirty years (1973-2004), under the direction of Sergio Donadoni (1973-1989), and then of Alessandro Roccati (1989-2004). During this extended time span, the excavations focused on two main sectors — one at the edges of the cultivated land, the other closer to the mountain and just north of the great temple area — bringing to light a number of important structures of both sacred and palatial character, which belong to the Meroitic phase of the site.

Autograph letter of P. Giovanni Vantini to Sergio Donadoni (13 February 1973), in which the missionary provides various logistic information (transferal of the equipment; cost of workforce; rental of a house for the mission in Karima) before the campaign 1973 (Archive MVOEM)

The Meroitic Temples

The first years of excavation (1973-1978) were dedicated to the investigation of two temple buildings (B1300 and B1400), which were identified at the south-eastern borders of the archaeological area, close to the fields. The decision was motivated by the threatened expansion of the cultivated land on the one hand and, on the other, by the fact that, unlike the core ceremonial area at the feet of the jebel, little was known of the larger layout of the city.

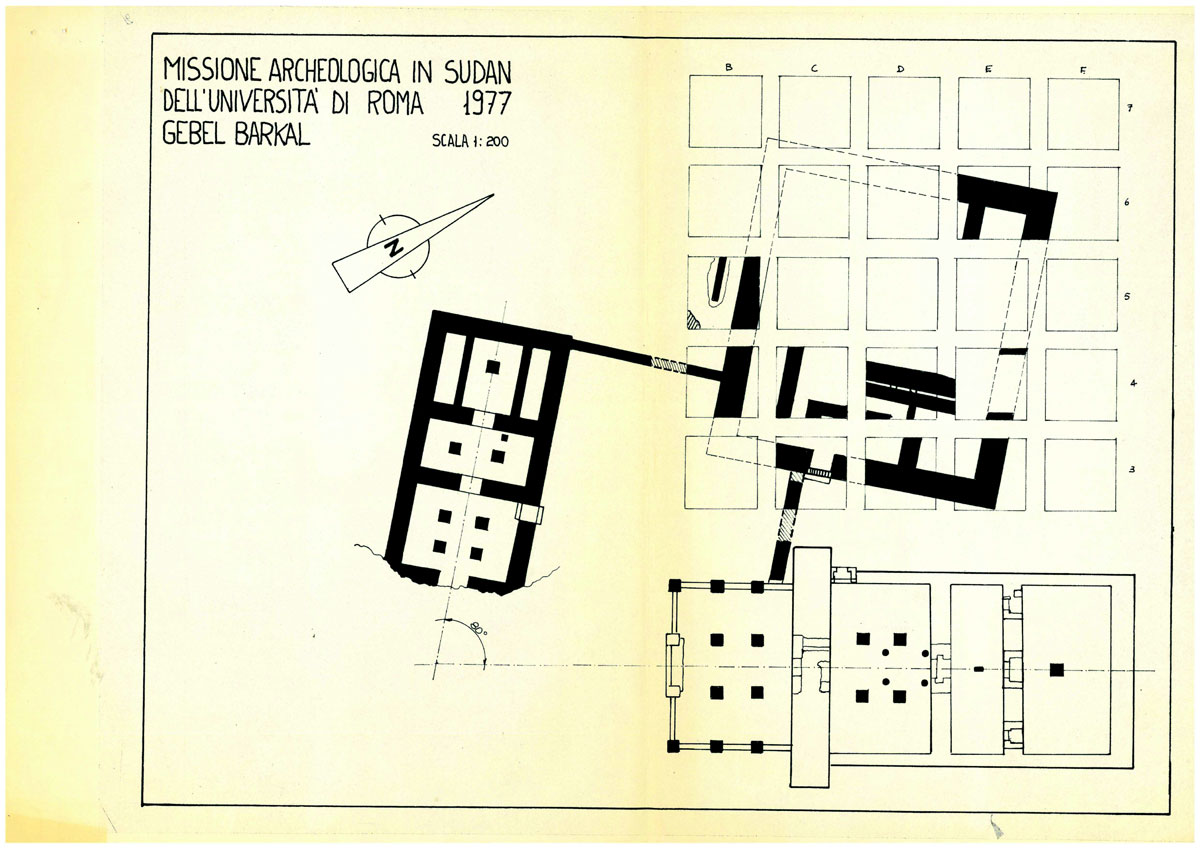

The two temples had different orientations and were built in different materials: B1300 was made of mudbricks and red bricks and followed a north-south axis, while B1400 was built in local sandstone and aligned east-west. On the other hand, despite being poorly preserved, the plan of both edifices was still visible on the ground, consisting of a regular sequence of pylon, pillared hall, vestibule, and tripartite sanctuary. Moreover, B1300 was accessed via a sort of porticoed gate preceding the pylon, while before the entrance of B1400 a platform made of fragments of sandstone, pebbles, pottery sherds and mud was identified.

Little survived of the original architecture and decoration of the two buildings, and few materials were recovered that could be useful for assessing the chronology and interpreting the identities of the gods to whom the temples were dedicated. The situation appeared more promising in the case of B1300, which was tentatively attributed to the Meroitic king Natakamani (first century CE) and associated with the cult of the god Amun on the basis of two significant findings. First, part of a decorated architrave belonging to the entrance of the pylon showed a king in front of a goddess identifiable as Mut, wife of Amun; the short accompanying texts gave the titles of the goddess and also recorded the praenomen of king Natakamani. Secondly, in 1976, in a corner of the sanctuary, two finely decorated ram heads in bronze (GB 76.1-2) were discovered, which were interpreted as the terminals of as many sceptres, evidently belonging to the cultic equipment of the innermost part of the temple. The significance relevance of the discovery was great, and given the delicate conditions of the two pieces, they were shipped to Italy and restored at the Centro di Restauro della Soprintendenza Archeologica della Toscana, similarly to what the Mission of Sapienza had previously done with the mural paintings from Sonqi. After that, in 1977, they were brought back to Khartoum.

Less clear, on the other hand, was the situation for B1400, where the only clue for its dating was the higher level of this building than that of the alleged Natakamani’s temple, a fact which would suggest a later chronological position than the latter, though only vaguely defined.

Ultimately, the enlargement of the excavations outside and beyond the two temples brought to light some mudbrick structures and deposits of material (mainly pottery), whose exact function and relationship with the temples could not be ascertained but seemed to indicate a wider (perhaps urban) layout and configuration.

General plan of the two temples B1300 (right) and B1400 (left), Archaeological Mission in Sudan University of Rome “La Sapienza” 1977 (Archive MVOEM)

Fragment of architrave inscribed with the prenomen of king Natakamani (Kheper-ka-ra) from temple B1300; April 1976 (Archive MVOEM)

Two bronze ram heads (GB 76/1-2) from temple B1300; March 1976 (Archive MVOEM)

The Palace of Natakamani and Other Ceremonial Buildings

From 1978 onwards, the excavations shifted back toward the mountain, to an area where sparse architectural remains visible on the surface suggested the presence of some monumental building. The choice proved to be fruitful since it led to the discovery of an impressive structure, labelled as B1500. At first thought to be a temple, it was then identified as a royal palace of square plan, standing over a mudbrick platform with a side measurement of 61 m and a preserved height of almost 2 m. The edifice became the main focus of Sapienza’s investigation for the following decades, and was put at the centre of intense excavation and restoration activity that aimed at reconstructing its layout and architectural history.

Aerial view looking south at the “Palace of Natakamani” (B1500) (Archive MVOEM)

Dominating the surrounding area, the palace showed a complex planimetric articulation developed around a central hall, while four monumental points of access were located on each side of the platform. The architectural decoration was extremely rich, including both stone features (doorway elements, cornices, capitals, bases and drums of columns) and a particular group of decorated glazed tiles, many examples of which were found during the excavations. Of special value, within this programme, was a number of lion statues sculpted in sandstone, which were recovered on the ground close to the monumental entrances and thus were probably originally placed to guard and decorate the points of access to the palace. Three of these statues are now stored at the Jebel Barkal Museum, a copy of one of them was made and is now displayed in Sapienza’s Museum of Near East, Egypt and the Mediterranean (MVOEM).

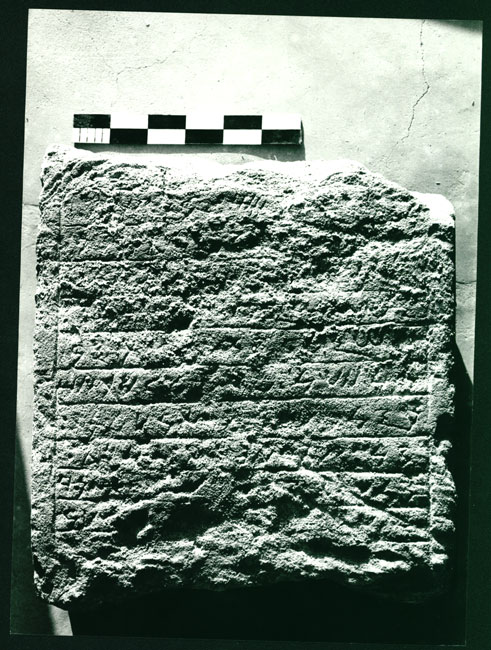

The constant progress of the excavations produced a better understanding of the chronological and historical position of the palace. While the analysis of the archaeological material and of the decorative programme indicated a clear attribution to the Meroitic period, the discovery in 1984 of a sandstone stela inscribed in Meroitic enabled a more precise dating of the complex. Though partially damaged, the text mentions the names of Amanitore and Arikhankharer (queen and son of Natakamani), thus offering an accurate date (first century CE) and possibly an individual figure for the construction of the palace, which since then has become known as the ‘Palace of Natakamani’. Given the importance of this epigraphic monument, a copy of the stela was made and it is now part of the collection of the MVOEM.

Stela of Natakamani (first Cent. CE); 1984 (Archive MVOEM)

However remarkable, the palace was not an isolated edifice, rather it was part of a larger building programme. In the last years of Sapienza’s excavations (2001-2004), some of these structures were identified (B2400; B3200), though the exact topographical and chronological relationships between them await further clarification. Most probably ceremonial buildings, their investigation and restoration has been carried out by other missions.

Jebel Barkal after Sapienza

Having moved to the University of Turin in 2005, under the supervision of Alessandro Roccati, since 2011 the direction of the archaeological activities at the site has been taken up by Emanuele Ciampini of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. This shift has coincided with a renewed investigation project that aims at (1) completing the excavation of the palace B1500 and its restoration; (2) extending the archaeological exploration to the surrounding area, where new structures of the royal district have been identified; and (3) processing and reassessing the information originating from the study of earlier documentation (https://sites.google.com/view/egittologiavenezia/scavo).