Christ Pantokrator, eastern wall of the haikal (room 2)

The Excavation of Sonqi Tino and the Official Birth of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Sudan

In 1967, within the framework of the previously-mentioned programme promoted by UNESCO for the exploration and rescue of the archaeological heritage in the desert region of the Batn el-Hajar (“belly of the stones”), Sapienza University started working at a Christian site that had been identified as 21-D-5 Sonqi West during the 1963-1964 reconnaissance survey conducted by UNESCO – Sudan Antiquities Service. Located on the west bank of the Nile, about 150 km south of Wadi Halfa, almost at the southern border of the second cataract, the site had been briefly recorded as including a small mudbrick church with possibly well-preserved paintings that were partially visible under the sand.

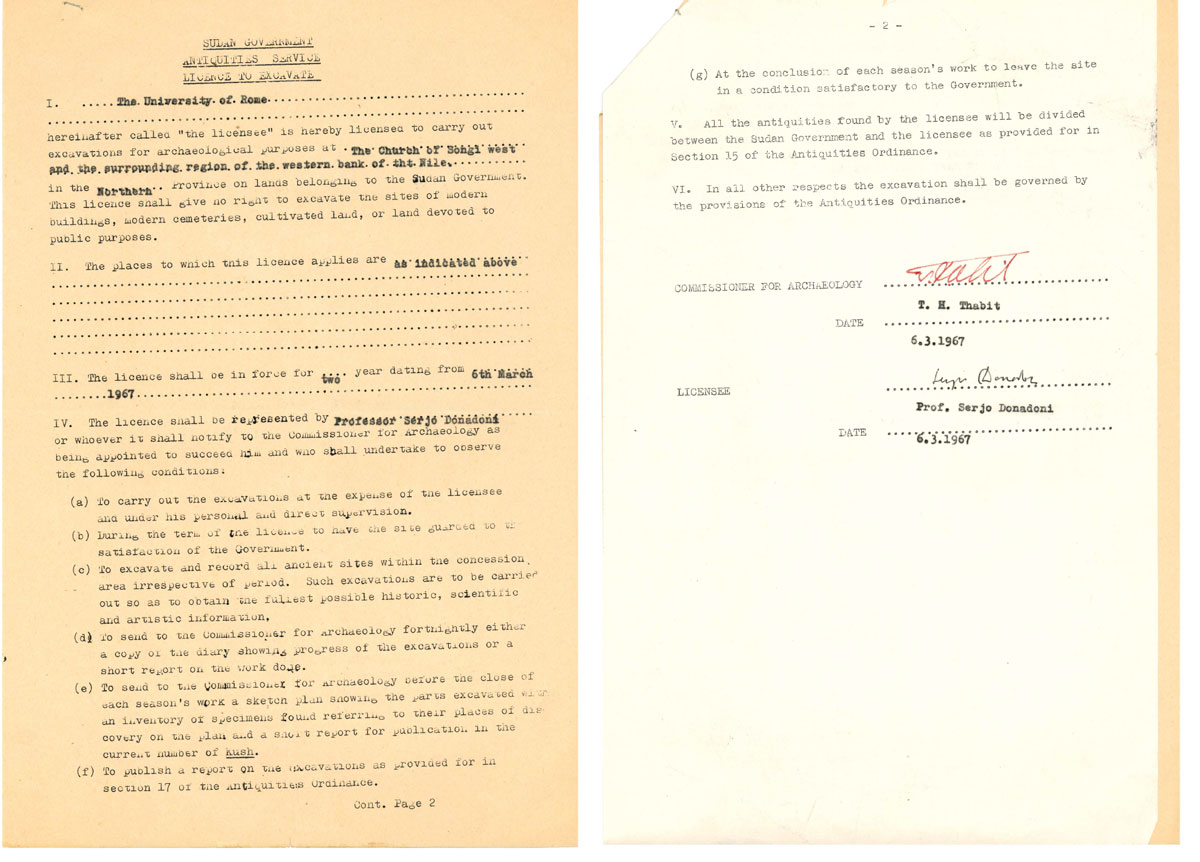

In March 1967, after a preliminary survey conducted by Sergio Donadoni and Sergio Bosticco in 1966, Sapienza obtained the licence to excavate, record, and document the site from the Sudanese Antiquities Service, directed by Thabit Hassan Thabit. The first Missione Archeologica Italiana in Sudan was then launched. The new enterprise also benefited from the important support of the Italian Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (C.N.R.) and that of the Vatican State. The mission, led by Sergio Donadoni, was composed of a high profile interdisciplinary team, including: Sergio Bosticco, Ida Baldassarre, and Giovanni Uggeri (archaeologists); Giuseppe Fanfoni and Italo Montalto (architects); Leonetto Tintori and Silvestro Castellani (restorers). To this group, the scholar and Nubian specialist P. Giovanni Vantini was added to represent the Holy See. Finally, an interesting note concerns the employment of a group of the well-known Qufti workmen (descendants of the Egyptian excavators from the village of Quft, who had been trained originally by Flinders Petrie), whose expertise was explicitly required.

As a first act, it was decided to change the name of the site into its Nubian form – Sonqi Tino –, a conventional designation used in literature since that time. Contrary to the initial expectations expressed in the the UNESCO report that the investigation of Sonqi West would have required only a few days or weeks to clean the church and remove the paintings, the archaeological activities carried out by Sapienza took four consecutive missions (1967-1970). Though short, these missions were extremely intense, not just because of the painstaking fieldwork and delicate activities related to the preservation of the church paintings, but also due to the remote and barely accessible location of the place, which required scrupulous arrangements.

The first expedition took place from 14 to 31 March 1967 and focused on clearing and exposing the basic layout of the church as well as on preparing a first stage in the recovery of the paintings. The surrounding region was also explored, and the so-called Diff (“Castle”) nearby was cleared and mapped. The task of preserving the painting was also the primary goal of the second season (21 February – 21 March 1968), together with the study of the architecture of the church. The two following expeditions (15 March – 3 April 1969; 3-20 March 1970) were dedicated to completing the excavation and the historical-architectural study of the church, and to exploring the structures nearby, in particular the adjoining cemetery.

Closing the final season in 1970, Donadoni summarised the results and expectations of Sapienza’s mission as follows:

What we considered our main task has seemingly been fulfilled: our Mission detected and secured the paintings in the first two seasons; it discovered and studied the architecture in the two following ones. We believe we are now ready to publish our study on this important monument

(Report 1970).

The licence of excavation of the site of Sonqi Tino signed by Thabit Hassan Thabit (Sudanese Antiquities Service) and Sergio Donadoni (Sapienza University of Rome), March 1967

Not Only the Church: Sonqi Tino and Its Surroundings

At the moment of the discovery, the church building, placed on a sand plateau close and high above the Nile, was almost entirely filled with drift sand up to the roof level. It was soon recognised as the most important monument in the area, and became the focus of Sapienza’s activities, being carefully excavated, mapped, and documented in the following seasons.

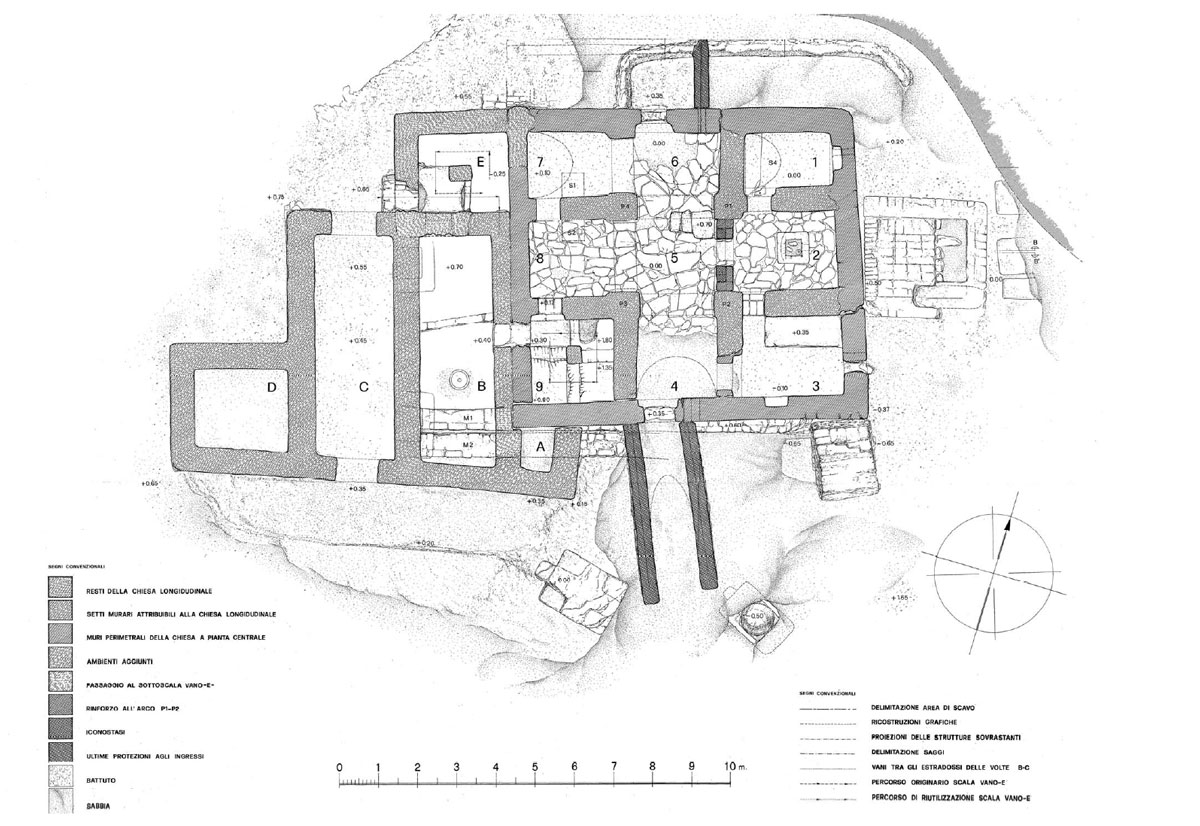

The church consisted of a mudbrick square building (9.30 x 8.30 m), which was subsequently enlarged with the addition of later structures. Its plan included nine rooms arranged according to a well-known cruciform pattern that had its fulcrum in a central room (5), open on its four sides and covered by a dome, while all the others were roofed with barrel vaults. The liturgical value of this layout was also materially emphasised by the fact that the chambers composing the two arms of the cross, which roughly followed an east-west and north-south axis, were paved in stone. The room at the eastern end (2) was the haikal, where a mudbrick altar was found still in place; scratched on its plastered surface, the excavators identified the name ΜΙΧΑΗΛ (Michael), to whom – they suggested – the church was probably dedicated. A remarkable feature was also the discovery of a pottery censer and two foundation stones, which had been deposited inside the altar. The following central room (5) formed, together with the one at the opposite western end (8), the nave of the church, while the two vestibules opening on its northern (6) and southern (4) sides served as the entrances to the building, looking respectively toward the desert and toward the river.

The four remaining rooms completing the plan had service functions and were thus not marked by a stone-lined pavement. On the east side, the haikal was flanked by, and communicated with, two chambers that were identified as the prothesis to the north (1), and the diakonikon (3) to the south; on the west side, room 7 was the only one found with the vault still intact, while room 9 contained a staircase that originally would have given access to the terrace upstairs.

To this core complex was added, on the west side and in a later phase of the church, a group of elongated structures, including a xenodocheion for accommodating visitors and pilgrims (A-D). The progress of the excavations also highlighted a number of restorations and repairs (mostly due to the instability of the ground and the lack of solid foundations) of great importance for understanding the architectural history of the building – a history that, as Donadoni himself recorded in 1968, “is far from being homogeneous”. Indeed, the analysis of the unearthed structures, briefly sketched out in the final report, and then refined by the study of Giuseppe Fanfoni (Sonqi Tino I) has allowed the identification of multiple building phases over the life of the church, including an earlier one, during which it had a basilica plan, and various later renovations.

Dating such a complex history is not an easy task, but the material recovered, especially the inscriptions and the paintings, suggest an attribution of the main phase of the church to the tenth century.

While central to the history of the site, the church of Sonqi Tino was not an isolated edifice, but was set within a larger context. In this regard, an important achievement of the four-year fieldwork was the exploration of a number of structures, features, and localities surrounding the church. These included a cluster of buildings to the north, which were excavated in the last two seasons and interpreted as residential units, and a group of tombs located to the south-east, which combined square plans with rectangular structures and spherical elements. They belonged to the local cemetery and were probably associated with a late phase of the church. In addition, there were two small settlements not far from the church (to the south), together with the fortified settlement of the Diff, further to the south.

Room 2 filled by drift sand at the time of the excavation, with painted decoration still in place on the eastern wall showing the image of the Archangel Michael

General plan of church building (G. Fanfoni, Sonqi Tino I, Roma 1979, Pl. 2)

The Decoration of the Church: Paintings and Inscriptions

The main undertaking, and the greatest achievement, of Sapienza’s work at Sonqi was the identification and recovery of the mural paintings decorating the church. Indeed, as Donadoni commented in the 1968 report,

what gave this little church a peculiar character was its lavish pictorial decoration.

The distribution of the paintings seems to have mainly affected the rooms that composed the cruciform layout (rooms 2, 4, 5, 6, 8), and in part also the two pastophoria (room 1, 3). The iconographic programme included representations of divine/royal figures (the Pantokrator from the haikal; Christ protecting king Georgios from room 8) and icons (the Holy Trinity on the eastern pillar between room 5 and 6) as well as of Biblical episodes (the Nativity from room 4; the Three Hebrews in the furnace from room 6). All these themes, well-attested within the framework of Nubian Christianity, find analogies with the painted decoration from other churches, like Faras, Abd el-Gadir, Tamit.

Their dating can be fixed with confidence to the second half of the tenth century, as it is confirmed by the inscription accompanying the group showing Christ protecting a king in room 8, which mentions “Georgios the son of Zacharias”. The identification of the king with Georgios II (r. before 969) indicates, in both cases, that the composition of pictorial cycle coincided with the main architectural phase of the church.

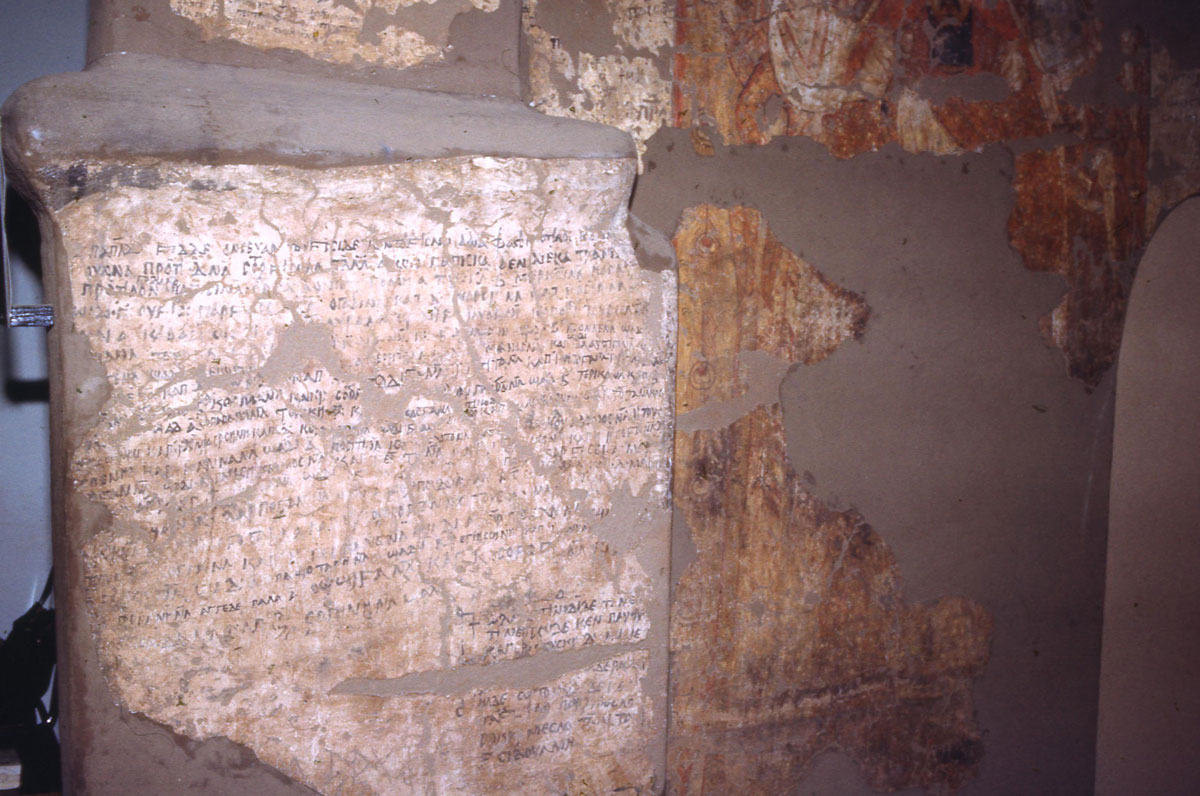

Together with the paintings, the exploration of the monument also recorded a number of inscriptions on the walls of the church. Painted or scratched on the plaster, the corpus included texts of different length and content (from the simple mention of names and titles to longer official inscriptions by prominent figures), written in both Greek and Old Nubian, thus illustrating the frequentation of the site and the multilingualism of contemporary society.

Christ protecting king Georgios “son of Zacharias” (room 8), Sudan National Museum

Long painted inscription from room 8, Sudan National Museum

The Restoration of the Paintings: An Italian Success

From the start of the excavations, it appeared that the preservation of the mural paintings inside the church was at risk, having suffered from the partial collapse of the masonry and from the roots of the vegetation growing in the area. Their recovery and restoration, therefore, was a top priority. The work to detach and consolidate the wall paintings was carried out by the famous Italian restorer Leonetto Tintori, with the collaboration of Silvestro Castellani. The operations were as difficult as they were delicate, given the harsh environment, and their transportation raised no fewer problems, since they had to travel along desert trails before reaching the train-station at Wadi Halfa and being shipped to Italy.

Having finally arrived in Florence, the paintings were restored in the laboratories at the Uffizi by Tintori himself, who consolidated them and applied light supports. In a letter to Giovanni Vantini (January 20th 1968), Donadoni described the result as follows:

As for the restoration, it seems to me that a greater care for the original conditions could not have been attained. The type of painting, its original quality, the very damages suffered ab antiquo, the graffiti, the inscriptions – everything is (to me) perfect.

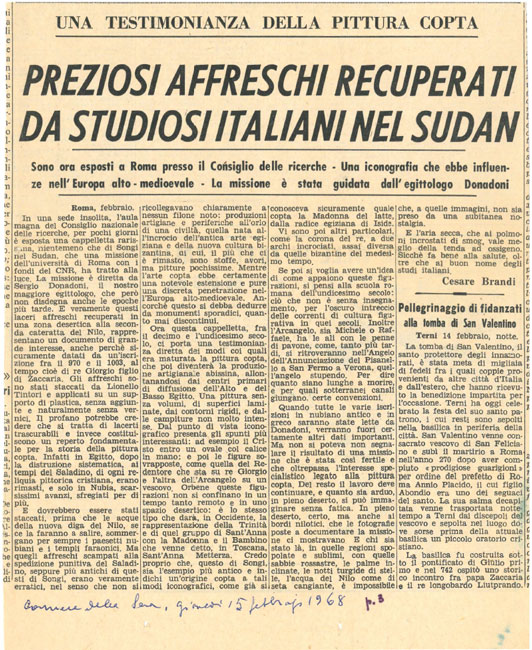

After completing the work, and before returning them to the Sudanese authorities, it was decided to display the restored paintings in an official exhibition that took place from 9 to 15 February 1968 at the Aula Magna of the Italian C.N.R. in Rome. In reporting the event in a letter to the then head of the Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Cairo, Carla Burri, Donadoni gracefully commented that it was a success, both for the material presented and the arrangement,

thanks to Tintori, in the first place, but also to Fanfoni and Montalto, who did their best and succeeded in changing a Mussolinian hall with genii à foison on the walls in a room where one cannot but admire what has to be seen

(February 10th 1968).

The exhibition received wide coverage in both the Italian and international media, but, above all, it was a unique chance for scholars – in the words of Donadoni –

to have a direct glimpse of this material which, beside that from Faras (Sudan) held at Warsaw, is rarely appreciable in European Museum”

As a result of all the efforts, the Sudanese authorities donated half of the recovered paintings to Italy, namely eighteen to Sapienza University, which are now displayed in what is today the Museum of Near East, Egypt and the Mediterranean, and one to the Vatican Museums. The remainder (eighteen) stayed in Sudan, where they entered the collection of the Sudan National Museum of Khartoum.

Article of the art historian Cesare Brandi on the exhibition of the paintings of Sonqi Tino at the C.N.R., Corriere della Sera of 15 February 1968 (Archive MVOEM)

Sonqi Tino in the Third Millennium: An Interdisciplinary Approach

On 21 February 2012, after almost fifty years since the discovery of the church of Sonqi Tino and since the first exhibition of its decoration, Sapienza and C.N.R. organised, under the coordination of Loredana Sist, a new event – The Nubian Church of Soni Tino: a multidisciplinary approach – that aimed to reassess the condition of the paintings and their context in the light of a detailed programme of screening, analysis, and restoration. The conference was an opportunity to present the results of the project as well as some updating and refinement on various issues, from chronology, to material culture, to landscape. Above all, the event demonstrated, specifically in relation to Nubia, the tremendous benefits that can be achieved by historical inquiry collaborating with a range of expertise combining the archaeological perspective with a detailed archival research and the potential of modern diagnostic technologies.